Sort “greatest monopolies immediately” into your Google search bar and click on. What are you able to anticipate finding close to the highest of the record?

You guessed it: Google. Like Customary Oil and AT&T earlier than authorities antitrust legal guidelines broke them up in 1911 and 1984 respectively, the net search engine completely dominates its trade—a lot in order that its title has develop into the verb for on-line looking out.

Whether or not Google meets an analogous destiny stays to be seen as antitrust fits wind their means via the system. Amazon, Fb, Dwell Nation Leisure, and different megaliths may additionally find yourself on the chopping block.

However is it essentially totally different when there are two dominant gamers?

Contemplate Coke and Pepsi, Visa and Mastercard, Apple and Samsung, Airbus and Boeing. Are these giants actually in competitors with each other, or are they merely going via the motions in a sort of symbiotic dance whereas blocking third-party rivals from getting a big piece of the motion?

And, talking of third parties: What concerning the Republicans and the Democrats? Collectively, don’t they’ve a dying grip on the political course of so agency that outsiders and independents have virtually no hope of mounting a critical problem? Given the titanic unpopularity of nominees heading each tickets over the newest election cycles, it’s debatable that the entrenched management amongst donkeys and elephants is much less interested by successful specific elections than in preserving affect over their respective energy bases.

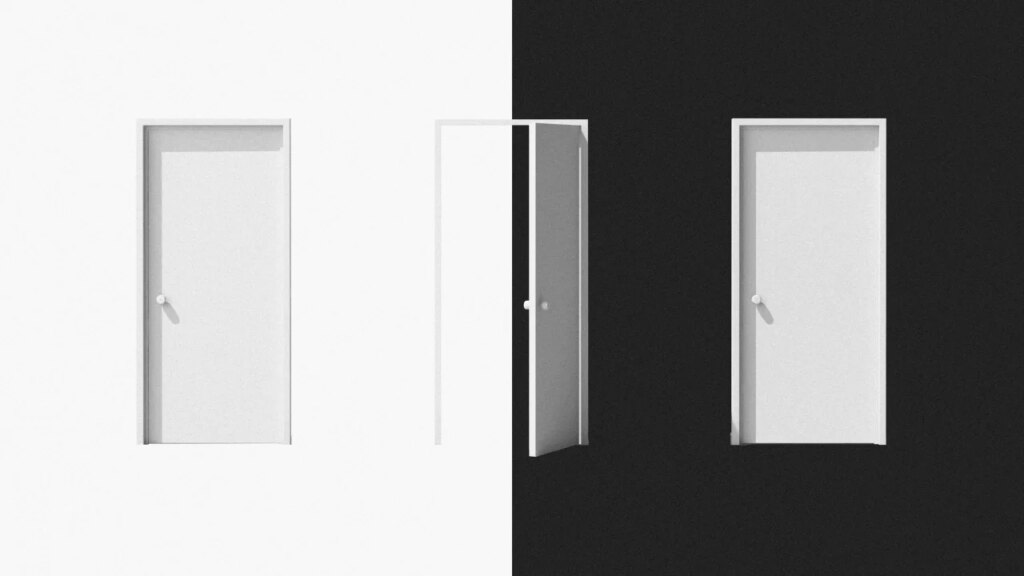

So what do you name it when not one however two entities declare an unfair benefit by excluding all contenders? Not a monopoly, however this week’s addition to the Moral Lexicon:

Duopoly (du·op·o·ly/ doo-op-uh-lee) noun

A state of affairs through which a commodity or service is managed by solely two producers or suppliers.

In a latest episode of Freakonomics Radio, host Stephen Dubner gathered thinkers and students to stipulate how the phantasm of competitors truly advances the consolidation of energy and dominance. By relentlessly vilifying the opposition, every candidate fuels tribalization by inflaming fanatical and passionate loyalty amongst their respective bases.

What’s extra, their flagrant exaggerations and disrespect for details exploit information shops, which give free promoting by dutifully carrying tales of battle and rivalry. Ultimately, most of us default to at least one occasion or the opposite, regardless of how dissatisfied we’re with our selection.

It’s not a lot totally different in enterprise. As a lot as we make a present of celebrating “disrupters,” the reality is we solely like them once they’re disrupting another person.

Let’s be sincere: Don’t all of us really feel the magnetic, emotional pull of brand name names—even when we now have to pay a premium? Aren’t we cautious of experimenting with new, untested services and products? Higher to let others take the chance after which leap on board if all goes effectively.

However how is that any totally different from our unwillingness to vote for third-party candidates? We complain concerning the system, however more often than not we’re complicit in perpetuating it.

Herein lies the insidious hazard of duopoly: It lulls us into the comforting fantasy that we’re exercising free selection, when the truth is we’re locked right into a misleading dichotomy between distinctions with none distinction.

Even worse, by whitewashing the lesser of two evils, we situation ourselves to indulge within the black-and-white pondering that daunts creativity. Ultimately, we blind ourselves from recognizing the moral perspective that seeks new and extra advantageous choices past the binary established order.

In his entertaining TED Discuss, “Why we make bad decisions,” Harvard psychology professor Dan Gilbert provides the next illustration:

You see a $2,000 Hawaiian trip bundle marketed on sale for $1,600. You’re pondering of going to Hawaii, so that you eagerly purchase it. However in the event you had seen the identical bundle on sale for $700 and now the worth has gone as much as $1,500, you most likely wouldn’t purchase it.

“In different phrases,” explains Professor Gilbert, “an excellent deal that was a terrific deal just isn’t practically as engaging as an terrible deal that was as soon as a horrible deal.”

The pure laziness of our brains inclines us to take pleasure in false comparisons somewhat than precisely and objectively assessing goal worth. If we discover possibility A detestable, our unconscious minds rapidly embrace any out there excuse to make possibility B look extra interesting, even whether it is barely a smidgen much less malignant than possibility A.

Typically, there actually are solely two choices, through which case we would have to carry our nostril and certainly choose the lesser of two evils. However that’s totally totally different from deluding ourselves into believing that an terrible selection just isn’t so dangerous as a result of it’s much less terrible than the plain various. By recognizing that false binary and rejecting the duopoly of our pondering, we open ourselves to the opportunity of a greater third means which may not be terrible in any respect.