This text is republished with permission from Blood within the Machine, a publication about AI, Silicon Valley, labor, and energy. Subscribe here.

Halloween is upon us, which suggests it’s a superb excuse to look at some movies from considered one of cinema’s most underneath appreciated genres: science fiction horror.

As I argued years ago, it’s a disgrace that there’s one thing of a dearth of these things. Hollywood is reluctant to the touch it, which is sensible, since sci-fi normally desires a giant finances, whereas most horror movies, by advantage of being horror movies, routinely restrict their potential audiences. Fortuitously, sci-fi horror nonetheless will get greenlit in tinseltown every so often, and unbiased studios and administrators discover methods to make it work—and when it really works, it actually works.

Not simply because filmmakers can actually push aesthetic and tonal boundaries right here—that is the prime playground for Cronenbergian body horror and J-horror—however as a result of it’s one of the crucial efficient mediums by which to register a critique of tech and its company masters. To specific technological anxieties and convey injustices on visceral degree that even, say, studying sensible weblog posts by tech journalists can’t match. Particularly within the sub-subgenre of sci-fi horror that tackles tech, which is typically known as “techno-horror,” although I have a tendency to withstand this time period, because it sounds a bit an excessive amount of like one thing which may occur at a Skrillex live performance. I favor ‘luddite horror.’

As common readers of my newsletter know, the actual Luddites weren’t dumb reactionaries who wished to smash machines as a result of they didn’t perceive them. They have been a well-organized and militant labor movement whose members absolutely grasped the risk sure machines posed to their livelihoods, when utilized by manufacturing facility bosses to drive down wages and exploit baby labor. The Luddites had a livid critique of expertise, and so they additionally knew that if it was getting used to oppress or exploit, typically the ethical factor to do was to destroy it.

Sci-fi horror is a style significantly adept at channeling such ethical rage, and expressing that intestine feeling of dread and injustice that textual critique merely can’t attain, particularly not at scale. It’s one factor to say ‘company AI might be harmful’ and it’s one other to eternally think about the foot of a T-800 crushing a human cranium. And whereas loads such movies are blunt and successfully attraction to our lizard brains, a number of luddite horror movies have sharp, even nuanced critiques of tech, too.

So, as I used to be pulling myself out of a stupor, and avoiding social media just like the plague, lest my blood strain spike and induce one other journey to the lavatory, I assembled this listing of important luddite horror movies; movies that problem, critique, or in any other case got down to smash the equipment hurtful to commonality. They vary from classics you’ve in all probability already seen a number of occasions to the obscure and sometimes grotesque and obscene. Since we’re speaking luddite horror right here, a few of the all-time classics within the sci-fi horror style received’t make an look—sci-fi horror movies like The Factor, Invasion of the Physique Snatchers, and The Platform have loads of crucial meat on their bones, however their chief targets aren’t tech. And I’m certain I’ve missed some, so do depart your favorites within the feedback—and this Halloween, add some machine-breaking to your horror combine.

‘Occasion Horizon’ (1997)

Arguably the gold customary for horror movies set in area whose titles don’t rhyme with mammalian, if solely as a result of the competitors for mentioned class is generally restricted to shark-jumping Leprechaun and Friday the 13th sequels. Occasion Horizon, well-known each for flopping upon launch and for that scene where they watch the tapes of the ship’s final crew tearing out their eyeballs and doing different such scholar movie violence to one another, additionally occurs to hold one of many largest and bluntest “man shouldn’t mindlessly meddle with expertise” messages in horror.

It is because Occasion Horizon is basically a Frankenstein film that takes place in Neptune’s orbit, with the complete hell-traversing, semi-sentient titular spaceship taking up the function of the Monster, and Sam Neil’s Dr. Weir character and a behind-the-scenes U.S. authorities sitting in for Dr. Frankenstein. See, Weir designed the Occasion to bend the legal guidelines of spacetime itself, and wound up opening a portal to hell—most Frankenstein, you would say, when it comes to reckless sowing and humanity reaping. What makes this a superb Luddite horror movie is that our chief protagonist, Laurence Fishburne’s Captain Miller, takes one look these tapes and makes the proper ethical choice to fireplace each missile he can on the Occasion Horizon. Weir, even earlier than he will get possessed by the ship/demon, is devoted to making an attempt to salvage the hell portal. Fortuitously, Miller succeeds in destroying Weir and a lot of the ship, probably sending all of them to hell within the course of. However the ultimate scene, by which one of many survivors has a imaginative and prescient of Weir returning, signifies that this impulse, to assemble units that would actually unleash hell on our world, has survived in spite of everything.

Double function: Hellraiser (1987). Okay, it’s sort of a stretch to name Hellraiser sci-fi, but it surely does function a tool, the Lament Configuration, that when opened guarantees to ship its customers ranges of ache and pleasure that transcend the earthly aircraft. And it implicitly comprises the concept that individuals who search it out will endure an eternity of hell and ache and may perhaps not try this.

‘Invisible Man’ (2020)

Invisible Man is a lowkey nice horror movie that shrewdly recalibrates a traditional franchise to execute a loaded satire of tech CEOs, poisonous masculinity, and (actually) invasive applied sciences. That is how reboots ought to be executed, in different phrases. If its reign wasn’t minimize brief by the 2020 pandemic lifeless 12 months for the movie trade, I wager its cultural imprint could be oh twice as large. It’s prime tier mainstream horror, expertly constructed, and in addition comprises what’s for my cash one of the crucial ‘holy shit’ scenes of the last decade to this point.

Elisabeth Moss’s Cecilia Kass is married to Adrian Griffin, an abusive, domineering tech CEO; she escapes their surveillance fortress of a house, then information breaks that Griffin has dedicated suicide, after which an invisible presence begins tormenting her in every single place she goes. The movie drew praise for Moss’s efficiency and the way in which it channelled the worry, PTSD, and gaslighting abuse victims endure day-after-day, and it’s simply as efficient at skewering tech titans. Griffin makes use of his huge wealth and leading edge “human augmentation” tech to surveil and torment his ex, prompting we viewers to interrogate why such issues are constructed and for whom. Higher but is the ending, by which the CEO tries to evade accountability for his crimes—his invisible man expertise offers him believable deniability—and Kass responds by taking issues into her personal palms.

Double function: Improve (2018) Director Leigh Whannell’s earlier function additionally guidelines; it’s extra of a violent revenge thriller than horror I suppose, but it surely equally places a malevolent tech titan in its crosshairs, and raises some questions on who AI is serving within the course of.

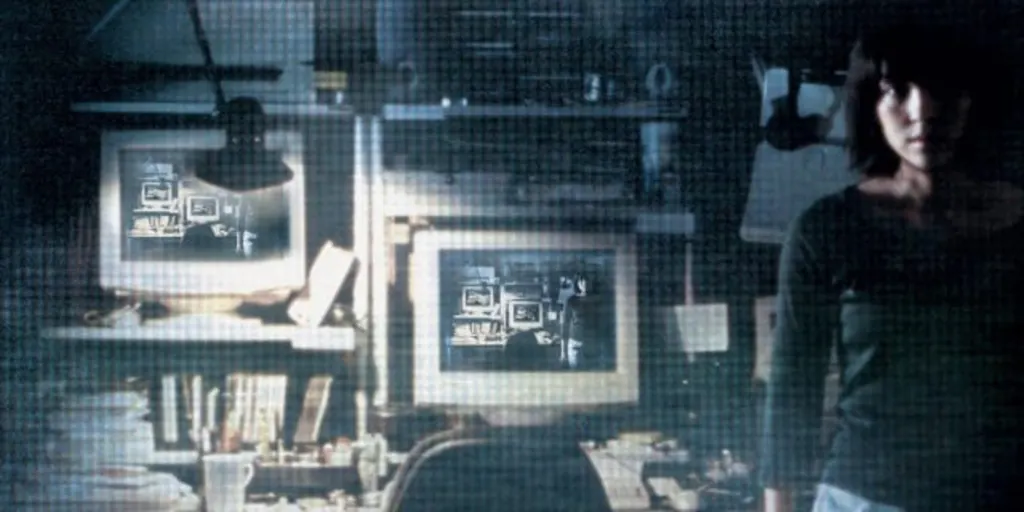

‘Ringu’ (1998)

Some 4 hundred years in the past when the Ring films have been a popular culture phenomenon and I used to be a youngster, I keep in mind everybody being extra fixated on the haunted ritual that gives the first plot mechanic—watch the cursed video, and also you’re lifeless in per week—and the scary visuals, and fewer on the reducing critique of media applied sciences that sits at its core. Which is truthful, it’s an important hook, a killer updating of the Bloody Mary fable, and who is aware of, I used to be a youngster, it’s attainable I missed a few of the crucial dialogue going down on the time. However what struck me on rewatching these movies extra lately is how immediately they transmit the theme that new applied sciences are certain to copy the traumas of the previous—solely extra violently, and extra frighteningly, as a result of our new applied sciences are ubiquitous. Each TV holds the potential of beaming in loss of life, each ringing phone a distant risk of violence. The supply of the destruction—the recorded anguish of an abused, disturbed and malevolent baby—is extra resonant than ever; the sort of darkness that, actual or imagined, animates the extra harrowing corners of the curdled on-line media ecosystem.

Ringu specifically holds up, at the least for individuals who retain the social context of VCRs and corded telephones, much more so than the American remake. 2002’s The Ring is, naturally, blunter and extra taken with leaning on inventory horror imagery and producing bounce scares, however continues to be nonetheless fairly strong. One distinction I seen; each movies have a scene the place the protagonist—a journalist and single mom in each—steps out onto the balcony of her sprawling condo advanced whereas her ex watches the cursed brief. In Ringu, she considers the economic sprawl, and the transmission infrastructure able to beaming in such horror; in the Ring, she seems in any respect the TVs which might be on in her neighbors’ residences. The ultimate twist, that the one solution to escape the video’s curse is to repeat it, at this time seems like a pitch black punchline—the way in which we survive is to grease the wheels, to share the cursed content material; you already know, to assist it go viral.

Double function: The Ring (2002). It’s nonetheless enjoyable and properly made, if distinctly hokier—strive to not cringe as Naomi Watts makes her entrance, saying herself as a hard-charging journalist by telling her editor to maintain his palms off her column. However the bounce scares that change Ringu’s brooding dread are fairly good, really.

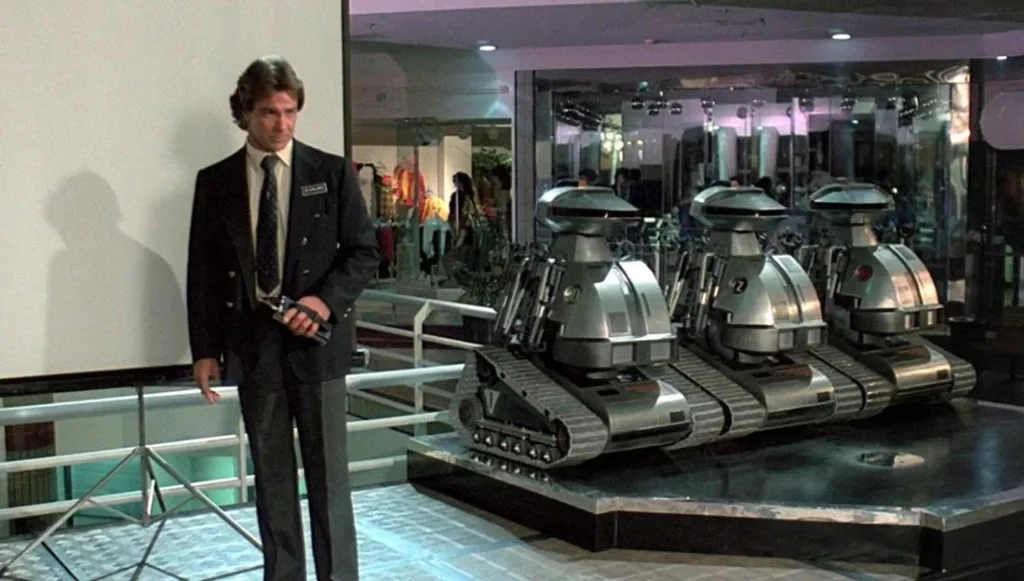

‘Chopping Mall’ (1986)

We’ve got to have at the least one ridiculous, deep B-movie horror movie on this listing, proper? Half RoboCop-esque Reagan-era consumerist satire, half low cost 80s slasher flick, and half Quick Circuit minus Steve Gutenberg, the misleadingly titled Chopping Mall greater than matches the invoice. A mall adopts a high-tech safety system designed to cease shoplifters, led by three armed “Protector” robots; it goes haywire and begins misidentifying youngsters partying on the mall after hours as intruders and killing them. It’s campy, self-aware, and is basically an prolonged screed towards privatized safety tech loaded with cartoonish violence. It additionally will get bonus factors for together with the very Luddite line, “Pc huh? Let’s go trash the fucker,” uttered when the teenagers set off to destroy the central surveillance system controlling the killer robots.

Double function: Daybreak of the Lifeless (1978). Maybe clearly, Romero’s sequel to Evening of the Dwelling Lifeless is by far the superior movie, and its satire of consumerism is funnier and extra pointed, however I don’t assume it fairly qualifies it as luddite horror, except you contemplate the mall itself a expertise, which—the case could possibly be made!

‘Threads’ (1984)

Ah Threads. Let’s simply come out with it: This is without doubt one of the bleakest and most viscerally affecting films you’ll ever watch. It’s much less a “horror movie” and extra simply “horrific,” and that’s as a result of it makes an attempt to methodically render, step-by-step, day-to-day, what a real-life nuclear holocaust would appear to be when the bombs began to fall.

Set within the thick of the Chilly Conflict, the nuclear powers snap, and the goal is Sheffield. So that you see the our bodies vaporized by the blast radius, the horribly burned additional out, the crazed and irradiated drive to outlive amongst these left, sifting via the wreckage, dying from radiation poisoning, or in the end freezing via the eventual nuclear winter. It’s not a discovered footage movie, however the impact is like watching a documentary of a future that was and is at all times a number of presses of a button away. That’s what makes it so very important—it forces you to inhabit such a future. If extra folks did, we’d really feel higher about our possibilities of it by no means coming to go.

Double function: Mad Max (1979). An excessive amount of its personal beast to be thought-about horror, the primary Mad Max, usually overshadowed by its larger octane siblings, presents a uniquely queasy and unsettling imaginative and prescient of the onset of the apocalypse.

‘Terminator’ (1984)

There’s a working argument amongst movie buffs that the primary Terminator is initially a horror movie—not like T2: Judgment Day and the next sequels, which function dramatic detours and motion scenes and extra science fictional exposition, the primary Terminator is nonstop dread, and Sarah Connor making an attempt to flee a monolithic killing machine programmed to kill her.

SkyNet is perhaps our most distinguished trendy Frankenstein; it’s common shorthand for AI run amok, and on this first movie it lurks within the suffocating undercurrent. There are a number of glimpses of the unspeakably grim future handing our fates to the machines, however they’re fleeting; future installments would construct out the contours of John Conner’s human resistance—a Luddite resistance, actually—however right here, our focus is laser-honed on Sarah, fleeing than preventing the relentless march of the lethal machine.

Double function: Metalhead (2017). This isn’t a film per se however a Black Mirror brief that stands alone to such a level it’s truthful to incorporate it right here. There’s little in the way in which of irony or satire or darkish twists that the present is thought for, only a relentless chase scene via an apocalyptic industrial wasteland, the place the pursuers are Boston Dynamic robotic canines set to kill on sight.

‘Cam’ (2018)

This considerate blast of indy horror guidelines, and looks like it didn’t get the eye it deserves, though it was produced by the trendy horror heavyweight studio Blumhouse. I don’t recall listening to a lot about it in any respect when it debuted in 2018. I found it via Naomi Klein’s guide Doppleganger, and I’m glad I did. The movie, which was written by a former cam performer, takes a pointy look not simply on the perils of on-line intercourse work, however of precarious digital work of each variety; the place the mad pursuit of rankings and microtransactions and at all times having to carry out a self for patrons. For creators, at all times having to push the envelope, to search out new and infrequently darker technique of drawing new audiences and sustaining fidgety outdated ones.

After which there’s the difficulty of digital identification, which provides the movie its central conceit—Lola, a rising performer on a well-liked cam web site, finds herself instantly locked out of her performer account, and a doppleganger there in her stead, making her cash. Lola’s struggles with a distant and ineffectual and possibly outsourced customer support rep, with the police, who dehumanize and barely register what she does for work in any respect, and with the rising sense of helplessness pervading her life, give the movie a pulsing sense of dread. I want the ending landed a bit extra, besides, that is biting Luddite horror.

Double function: Emily the Prison (2022). So that is undoubtedly not a “horror” movie, extra of a thriller, and in contrast to Cam, there’s no supernatural or sinister technological conceit. It’s only a actually good movie that packs the nervousness and precariousness of recent gig work into a strong and hectic narrative.

‘Tetsuo: the Iron Man’ (1989)

Simply essentially the most unhinged piece on this listing, this surrealist cyberpunk seizure of a movie can be perhaps the toughest to look at, each because of the queasy, rapid-fire enhancing and the horrifying visuals on display screen. There’s not a lot of a plot—a person who has simply inserted some sort of metallic system into his personal leg is the sufferer of successful and run, and each he and the motive force of the automobile who hit him watch their our bodies slowly turn out to be actually overtaken by metal, scrap, and wire. The result’s kind of like JG Ballard on acid—the motive force and his spouse have intercourse after the crash and disposing of the physique, in a nod to Crash—a visceral have a look at how we’re willfully shedding ourselves to expertise, by selection, by power, or by assimilation. Tetsuo’s frenetic visuals revel within the blind ecstasies and exhilaration of being consumed by an unsure kind of progress, and within the psychosexual attract of technological augmentation and violence (Spoiler: at one level the motive force’s genitals remodel right into a lethal drill). In the end, it appears to suggests the 2 most believable outcomes for a world by which our selves and our our bodies are overrun by industrial expertise is we both embrace its violent potential energy, or we turn out to be servile to it.

‘Private Shopper’ (2016)

With the rise of so-called griefbots, AI approximations of lifeless family members that startup founders say may help the bereaved address loss, it’s a superb time to take a look at this sleeper Kristin Stewart-starring ghost story. A singular, eerie, and melancholic movie, it follows Stewart’s character, who has simply misplaced her twin brother Lewis to a congenital coronary heart illness that she has, too. Working as a private shopper for a star in Paris, she seems for a sign from her brother, who promised he’d contact her, by some means, from the afterlife. She begins receiving textual content messages from an unknown sender, who she believes to be Lewis, and the movie solely will get darker and extra haunted from there. There’s a critique each of expertise and of consumerist want woven all through—even the video chat Stewart’s character logs together with her boyfriend, who’s working as a contractor in Oman, feels quietly cursed—and the way this stuff have distorted our potential to know ourselves, and what we really need. And oh man, that ending.

‘Eraserhead’ (1977)

Maybe no shock right here, however Eraserhead’s nonetheless bought it, almost 5 many years on. David Lynch grew to become well-known, almost to the purpose of parody, for analyzing the darkish underbelly of small city and suburban life. Eraserhead, nonetheless, is extra involved with the sickly results of industrialization and poverty. (And with childrearing after all, however we’re right here to speak Luddite horror.) Poor Henry Spencer should traverse lengthy hostile wastelands of business rubble anytime he goes out, he fixates on the imagined internal world of his radiator, since there isn’t a lot else to do, and is handled to a dinner of lab-grown rooster that oozes a sickly blood when carved.

There’s an interrogation, absent in quite a lot of Lynch’s future work, of how industrialization; our factories, our applied sciences; quantities to hell for the poor—how in an setting like that, the prospect of elevating a baby may appear as scary as rearing a wailing alien lizard. Greater than something, Lynch conjures a temper of dread of residing with little in such areas, the cacophonous thrumming of equipment at all times within the background, a grim holding out for the hope, that, because the radiator woman places it, “in heaven, the whole lot is okay, you’ve bought your good issues, and I’ve bought mine.”

‘Get Out’ (2017)

What makes Get Out Luddite horror? Tons: The movie’s large reveal is that white elites possess a expertise that may fairly actually reappropriate blackness—forcibly inserting a white mind in a black physique. All kinds of actual applied sciences are used to do that in the actual world, after all: social media platforms that harvest blackness for cultural cache, counting on black customers whereas firms that revenue from the content material rent few black staff. Which is to say nothing of the horrific applied sciences of the previous used for many years to regulate black our bodies and exploit their labor.

Get Out is a good horror movie, clearly—it deserves the accolades it’s obtained—and it’s a reminder that these applied sciences are nonetheless distinguished, nonetheless serving the highly effective, usually tucked simply out of sight, working underneath the floor, even because the highly effective are outwardly celebrating racial progress. As soon as once more, as protagonist Chris finds, the one surefire solution to push again is to combat, with vital power, towards the operators of such equipment.

Double function: Nope (2022). Jordan Peele’s third movie is much less narratively propulsive, maybe, its critique of racism much less barbed, but it surely’s an important movie, too, and takes intention on the equipment of Hollywood, and of manufacturing our stained and unequal myths.

‘Godzilla’ (1954)

I nonetheless keep in mind the primary time I noticed the unique theatrical minimize of Gojira, at a screening in New York—I used to be floored. I had at all times written Godzilla off because the hokey rubber-costumed creature function that at all times gave the impression to be exhibiting up in a single interchangeable sequel or one other on the deeper reaches of cable, preventing Mothra, or crab monsters, or no matter.

However if you happen to haven’t but, or if it’s been years and also you barely keep in mind it, go watch the unique. Made lower than a decade after Hiroshima, it’s such a strong airing out of the horror, grief, and shock of a nation traumatized after being devastated by the one most harmful expertise in human historical past. Godzilla is the gnashing hell unleashed by the bomb, after all, the populace of Tokyo fleeing in terror from its wrath. Even many years of cultural dilution and hammy monster matchups have executed nothing to blunt its energy.

Double function: The Host (2006). Bong Joon-ho’s creature function isn’t fairly a horror film, but it surely isn’t fairly the rest both. Humorous, darkish, and using a broadside towards industrial air pollution, anybody who dug Parasite can be into this one, too.

‘Pulse’ (2001)

That is perhaps the movie on this listing that the majority stuffed me with a way of sustained dread, which is de facto saying one thing. It additionally would possibly nonetheless be the perfect cinematic remedy of how the web and automation breed isolation and loneliness? Perhaps not simply in horror, however interval? 20 years after its launch, and lengthy after the web took over our lives? The following film down could have the last word declare to prescience with regards to critiquing how consuming technologically mediated content material would possibly have an effect on us, but it surely’s a tossup for certain, and both manner, Pulse is manner up there.

Pulse takes place within the early days of the web, when customers who come into contact with one thing known as the Forbidden Room start both disappearing solely, or killing themselves. There are haunting, disturbed pictures of the positioning, grainy video feeds of lonely folks staring into livestreamed webcams. There’s the cursed imagery when somebody disappears, claimed by the ghosts of the Forbidden Rooms. However much more stunningly, to me, there are the huge and haunted empty areas that the remaining characters occupy, in arcades and supermarkets (in what appears to be a cursed callout to the rise of self-checkout) and robotics labs. No, it doesn’t make sense, precisely (does the web?), however in a manner few movies have managed, it conveys the vacancy, the hollowness, and the potential for despair to come up from then-ascendent on-line networks. Most of us know somebody who we’ve ‘misplaced’ to the web’s darker areas, and there’s an epidemic of juvenile melancholy, stemming from the identical roots. Pulse noticed it coming.

‘Videodrome’ (1983)

Alright, let’s be sincere; this whole listing could possibly be in all probability be stuffed with David Cronenberg movies—The Fly, eXistenz, Scanners, and so forth all may have made the minimize—however I made a decision to restrict it to 1, and it was apparent which one it will be. It’s truthfully wild that, 4 many years in the past, Videodrome not solely anticipated the wicked race to the underside that media applied sciences, helmed by unscrupulous executives, would facilitate, however so successfully talk the feeling of being concurrently transfixed, repulsed, and hooked on the content material that will spew forth because of this.

There are such a lot of unbelievable touches within the movie—a shelter the place the unhoused are ushered into cubicles to look at TV, the recurring picture of the physique opening as much as actually devour a videotape, to devour content material, and the hallucinatory dream state the place violent and sexual impulses, impressed by the horrors we’ve witnessed on a display screen, are concurrently actual and unreal. Even the maxim made well-known by the movie rings with simple reality. It’s laborious to argue that the extraordinary digital mediation that’s totally entwined with our every day being has not basically altered us or how we expect. Lengthy stay the brand new flesh, certainly.

Triple function: The Fly (1986). eXistenz (1998). The Fly is nice, however you in all probability already know that; it’s one other traditional Frankenstein story, albeit very ugly and really shifting. eXistenz is much less seen, and got here out in one thing of a fallow interval for Cronenberg, but it surely takes on gaming and VR, and it’s fairly killer, too.

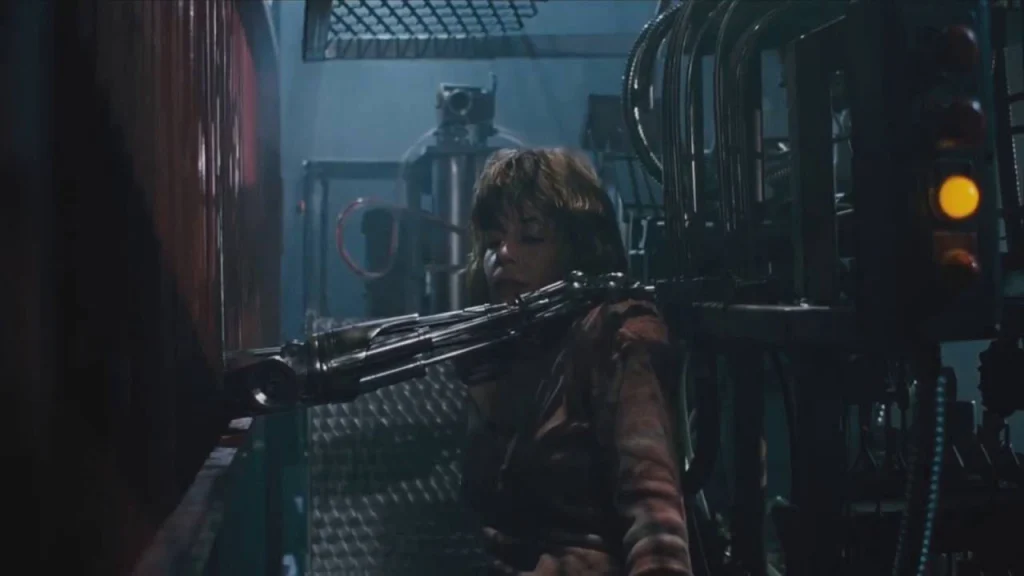

‘Alien’ (1979)

What else? The best science fiction horror movie of all time can be the best luddite horror movie of all time. Put apart the immortal HR Giger creature design, the notorious chest-burster scene, its immaculate pacing and all that, and also you’ve bought a largely blue collar crew of area rig employees thrust into the direst of horrors by company coverage—coverage that’s enforced by Mom, the ship’s AI, and Ash, the corporate android. Watching the movie once more lately, it’s bludgeoningly clear how central class politics are to the movie, and the way resonant they continue to be at this time. The primary dialogue within the movie regards a pay dispute between the lowest-paid employees—the mechanics—and administration. And a brooding sense of inevitability governs everybody’s actions, even the captain’s, who despairingly takes his orders from Mom.

The Nostromo crew has, in different phrases, been intensely surveilled and managed, by way of an AI, even deep into the reaches of outer area. Sigourney Weaver’s Ellen Ripley would turn out to be an iconic motion hero due to her distinctive potential to combat off the xenomorph, however she’s additionally the one one within the movie who stands as much as company energy, and to the expertise it owns—particularly the android Ash—which she continues to do in subsequent movies. She is iconic for placing humanity first, for preventing towards immensely worthwhile organic weaponry and highly effective company AI. Ellen Ripley is, in different phrases, one hell of a Luddite.

Septuple function: Aliens, Alien 3, Alien: Resurrection, Prometheus, Alien: Covenant, Alien: Romulus. What can I say? I like the Alien movies; they’re all price watching, none are “dangerous” and a few are nice. I’m even a Prometheus apologist. And these are all prime kind luddite horror movies.

This text is republished with permission from Blood within the Machine, a publication about AI, Silicon Valley, labor, and energy. Subscribe here.