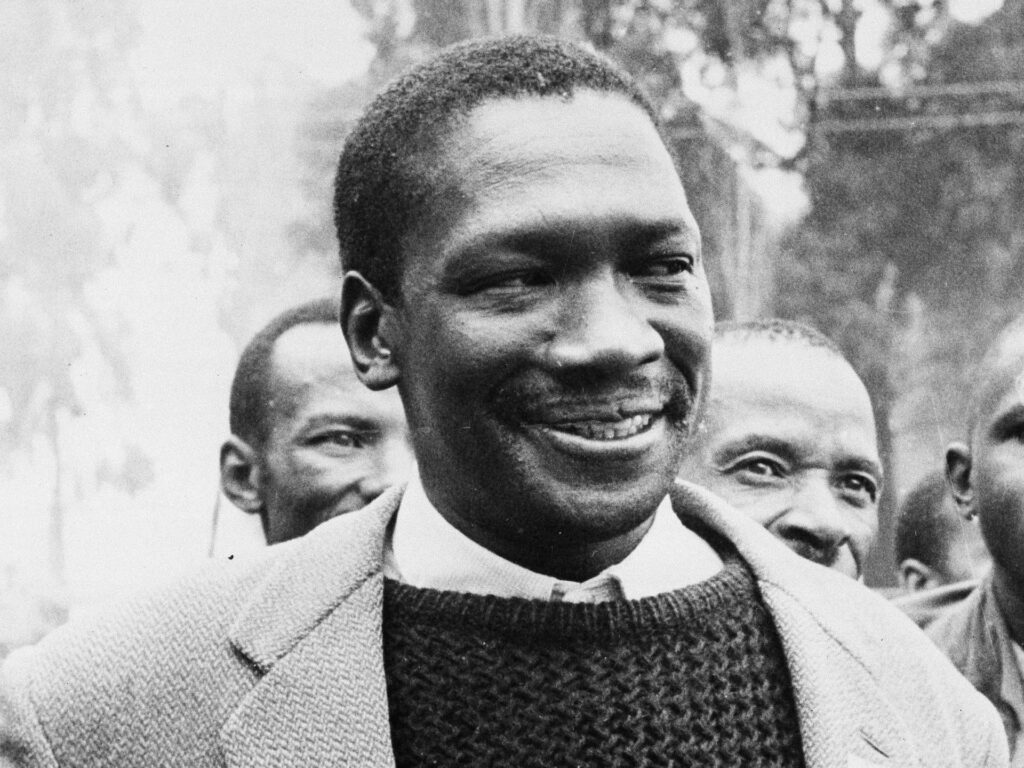

On Monday, March 21, 1960, Robert Sobukwe, the 35-year-old chief of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), woke at 5am. His spouse, Veronica, heated a kettle of water on the range, and he washed in a bathtub within the kitchen of their one-bedroom home in Soweto, the most important Black township in Johannesburg.

After getting dressed, he ate his common breakfast of eggs, bread, porridge, and tea. Someday after 6:30am, six males from the neighbourhood arrived and, favorite pipe in hand, Sobukwe kissed Veronica goodbye.

The lads walked in sombre silence as, round them, the folks of Soweto hurried to get to work. “Boys, we’re making historical past,” mentioned Sobukwe presciently – regardless of all appearances on the contrary. Think about their immense aid when, after an hour of strolling, they reached Soweto’s fundamental Orlando police station to search out scores extra PAC supporters already there.

The ambiance exterior the police station was jovial. “There have been smiles, proper palms raised in salute and cheerful shouts of ‘Izwe Lethu’ [‘the land is ours’, a PAC slogan] … PAC ladies from close by homes introduced espresso,” writes Benjamin Pogrund, Sobukwe’s lifelong pal and the creator of How Can Man Die Higher – a remarkably transferring e book that’s each a biography of Sobukwe and a chronicle of the enduring friendship between a liberal, white reporter and a Black political chief. (“I’ve mates, in fact, of whom I’m very fond,” Sobukwe as soon as wrote to Pogrund. “However I’ve lengthy handed the stage of even considering of you as a pal.”)

At about 8:20am, by which era the group had swelled to between 150 and 200 folks, Sobukwe and some others walked via the gates and knocked on the door of Captain JJ de Moist Steyn, the white officer in cost. “We have now no passes and we wish the police to arrest us,” mentioned Sobukwe, referring to the paperwork all Black folks had been required to hold in “white” areas. Throughout apartheid, previous violations noticed a whole bunch of hundreds of Black South Africans arrested yearly, for many years.

“I’m busy and you will need to wait a bit,” replied Steyn, irritated at being interrupted by, in his phrases, an “grownup Bantu man”. Some time later, Steyn went exterior to situation a warning to the group that had gathered on the grassy slope reverse the police station: “If there’s any interference with the execution of police work, there’s going to be bother.”

Whereas organising the nationwide anti-pass protest, Sobukwe had anticipated the potential for a heavy-handed police response. He had even written to the Commissioner of the South African Police on March 16 to warn of his plans to launch “a sustained, disciplined, non-violent marketing campaign towards the cross legal guidelines”.

Within the letter, Sobukwe requested the police to “chorus from actions which will result in violence”. As he defined, “it’s sadly true that many white policemen, introduced up within the racist hothouse of South Africa, regard themselves as champions of white supremacy and never as legislation officers … I due to this fact enchantment to you to instruct your males to not give not possible calls for to my folks … We are going to give up ourselves to the police for arrest. If informed to disperse, we are going to. However we can’t be anticipated to run helter-skelter as a result of a trigger-happy, African-hating younger white police officer has given hundreds … of individuals three minutes inside which to take away their our bodies from his instant setting.”

Outdoors the Orlando police station, Sobukwe and his followers waited on the garden within the morning solar. However his worst fears had been coming true elsewhere. Someday earlier than 11am, Pogrund got here to inform his “visibly upset” pal that at the least two PAC supporters had been killed by police at Bophelong, one of many townships exterior the commercial city of Vanderbijlpark, about 55km (34 miles) south of Orlando.

Shortly after Pogrund left Orlando to report on the rising tensions to the south, Sobukwe and a few of his supporters had been lastly arrested. He was pushed in a police van to the clinic the place Veronica labored as a nurse to gather his home keys. The cops proceeded to go looking his house and his workplace on the College of the Witwatersrand, the place he taught Xhosa and Zulu, seizing liberal magazines and different “subversive” materials. Someday after 1pm, Sobukwe was booked into Marshall Sq., Johannesburg’s central police station.

Unbeknownst to him, all hell was about to interrupt unfastened at Sharpeville, one other of Vanderbijlpark’s townships. Earlier that morning, between 5,000 and seven,000 Black South Africans who had marched to Sharpeville’s municipal workplaces had been met with tear gasoline and a police baton cost. They decamped to the police station and requested to be arrested – however the commanding officer mentioned he couldn’t lock up so many individuals.

Each element of what occurred subsequent is the topic of a lot dispute. The police report put the dimensions of the group at 20,000, whereas different estimates mentioned it was nearer to five,000. The police account pressured the hostility of the group, however witness accounts instructed in any other case. “A police officer mentioned he noticed a small gray automotive being swallowed up and thought the folks within the automotive had been being attacked,” wrote Pogrund. “However the truth is, that was my automotive and the demonstrators had been utterly pleasant.” Two different white journalists on the scene, Humphrey Tyler and Ian Berry, had been additionally struck by the friendliness of the group.

Whereas the protesters waited (there have been rumours {that a} authorities official would come to handle them) the police referred to as in reinforcements. At about 1:30pm, after police arrested one of many protesters, the group pushed towards the fence surrounding the station. As Pogrund writes, “one or maybe two policemen opened fireplace after which there was a full volley from revolvers, rifles and Sten-guns. No order to fireplace was given. The capturing went on for at the least forty seconds. A number of policemen, together with Sten-gunners, reloaded and fired once more.”

Tyler, who was nearer to the motion than Pogrund, wrote that the group was “grinning, cheerful and no one appeared to be afraid. Then the capturing began. A gun opened up toc-toc-toc and one other and one other … The primary rush was on us, after which previous. There have been a whole bunch of girls. A few of these folks had been laughing, most likely considering the police had been firing blanks. However they weren’t. Our bodies had been falling behind them and amongst them. One lady was hit about ten yards from our automotive. Her companion, a younger man, went again when she fell. He thought she had stumbled. He turned her over within the grass. Then he noticed that her chest was shot away.”

In complete 1,344 rounds had been fired into the group. The police report – repeated as truth till 2023 – put the variety of victims at 69 useless, together with 10 youngsters, and 180 injured. However latest research reveals that at the least 91 folks had been killed and 281 had been injured. Greater than three-quarters of the victims had been shot within the again as they tried to flee.

Three policemen had been barely injured by stones.

Sobukwe’s letter of warning had been ignored. And when information of the bloodbath filtered via to him in his cell in central Johannesburg, he was, in response to certainly one of his fellow inmates, “very upset. He had finished his greatest to make sure a really orderly and peaceable marketing campaign. How might so many die for saying they might now not carry the image of slavery?”

In opposition to the chances

Born as Robert Mangaliso – which means “it’s great” in isiXhosa (or Xhosa), his mom tongue – on December 5, 1924, in a Blacks-only location on the outskirts of Graaff-Reinet, a smallish sheep farming city in a forgotten nook of South Africa, Sobukwe was the youngest of seven youngsters of Angelina, a cook dinner and cleaner, and Hubert, a wool sorter and woodcutter. Angelina had by no means been to high school (her thumbprint served as her signature), however Hubert had accomplished seven years of main faculty earlier than his mom forbade him from enrolling at highschool. She thought being educated would lead him to disregard the wants of his household. “Hubert’s disappointment lived with him,” writes Pogrund, “and he made a vow: ought to God give him youngsters, he would educate all of them”.

The Sobukwe house had earth flooring and no electrical energy or operating water. The kids slept on mattresses original from wool luggage however their dad and mom noticed to it that they by no means lacked books. It labored. A minimum of three of the Sobukwe youngsters certified as lecturers and one was ordained as an Anglican bishop.

Robert was all the time an distinctive pupil. After finishing the free main faculty training out there in Graaff-Reinet, he was pressured to attend two years whereas his dad and mom mustered the cash to ship him to highschool at Healdtown, the identical prestigious Methodist boarding faculty Nelson Mandela attended. At Healdtown, he was identified “for his brilliance and his command of the English language”, mentioned classmate Dennis Siwisa.

After finishing his trainer coaching qualification – because of the shortcomings of the “native” training system, the bar was set very low for Black lecturers – the Healdtown workers inspired Sobukwe to not exit and earn a dwelling however to proceed his research. These plans had been placed on ice when, aged 18, he began coughing up blood. His father wished to take him house to die, however the faculty’s head trainer, George Caley, was capable of wrangle a mattress at a hospital specialising in tuberculosis.

As soon as Sobukwe had recovered, he was given a bursary by Healdtown, and Caley personally sponsored him with books and pocket cash. In his closing yr at Healdtown, he was the varsity’s head boy, signing off on the position with what Caley described as a “great” speech “about cooperation between whites and blacks”.

With the help of Caley, Sobukwe enrolled at Fort Hare – South Africa’s solely college for Black Africans, and the alma mater of Mandela and fellow anti-apartheid icons Oliver Tambo and Govan Mbeki amongst many others. When he arrived at Fort Hare, aged 23, Sobukwe was not remotely fascinated with politics. He was, recollects Siwisa, “a cheerful, contented individual” with an ideal love for literature.

Political awakening

A second-year course on Native Administration – the various legal guidelines that ruled life for Black South Africans – given by an clever and opinionated lecturer referred to as Cecil Ntloko, opened Sobukwe’s eyes to the inequalities that he, and anybody else together with his pores and skin color, confronted daily. He took that course in 1948: the identical yr that DF Malan’s apartheid authorities got here to energy.

The next yr, his final at Fort Hare, Sobukwe was elected president of the scholars’ consultant council. He additionally joined the African Nationwide Congress Youth League (ANCYL) – an offshoot of the ANC based by Mandela and others 5 years earlier.

Earlier than leaving Fort Hare, he as soon as once more signed off with a speech – however his concepts had come a great distance since Healdtown. In it, he implored Black South Africans to forge their very own future, a way forward for freedom and African unity.

“Folks don’t wish to see the even tenor of their lives disturbed,” he mentioned. “They don’t wish to be made to really feel responsible. They don’t wish to be informed that what they’ve all the time believed was proper is unsuitable. And above all, they resent encroachment on what they regard as their particular province. However I make no apologies. It’s meant that we communicate the reality earlier than we die.”

The speech, whose textual content has survived, was a spellbinding distinction with the a lot better-known Mandela’s public oration, which for probably the most half was comparatively boring. “It was too scorching!” remembered Ntloko, of Sobukwe’s Healdtown speech.

“I want to make it clear once more that we’re anti-nobody,” Sobukwe mentioned halfway via it. “We’re pro-Africa. We breathe, we stay, we dream Africa; as a result of Africa and humanity are inseparable … On the liberation of the African relies upon the entire world.”

When information of the speech, and its supposedly anti-white message reached Caley at Healdtown, it got here as a “dreadful shock”. The plan had all the time been for Sobukwe to return to Healdtown as a trainer – however now he must search for work elsewhere.

Africanists and Charterists

After two comparatively uneventful years of educating (he did virtually get fired for organising political conferences in his spare time) at a secondary faculty within the far-off farming city of Standerton, Sobukwe was supplied a job educating Zulu and Xhosa on the liberal, white College of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Whereas in Standerton, Sobukwe’s ties with the ANC had weakened considerably, however in Johannesburg – the epicentre of the wrestle – he was thrown again into the day by day affairs of the get together.

And he didn’t agree with every thing he noticed or heard. Sobukwe quickly fell in with an off-the-cuff grouping throughout the ANC who referred to as themselves “Africanists”. The Africanists had been fiercely anti-communist they usually had been against the ANC working with different color teams, as they felt that the wrestle needs to be “for Africans, by Africans”. When, in 1955, the ANC teamed up with congress actions representing different race teams to signal the Freedom Constitution – which declared “that South Africa belongs to all who stay in it, black and white” – it created a rift between the Africanists and the Charterists. This rift would culminate in Sobukwe and about 100 different Africanists splitting from the ANC in 1958, and forming the PAC a yr later.

In his autobiography, Mandela expressed disappointment on the behaviour of his “outdated pal” Sobukwe. “I discovered the views and behavior of the PAC immature … Whereas I sympathised with the views of the Africanists and as soon as shared lots of them, I believed that the liberty wrestle required one to make compromises.”

Sobukwe was unanimously elected as chief of the brand new get together. Whereas some within the ANC had accused him of being “anti-white” he cleared this up in a rousing opening handle on the Orlando Communal Corridor on April 4, 1959: “We intention, politically, at authorities of the Africans by the Africans, for the Africans, with everyone who owes his solely loyalty to Africa and who is ready to just accept the democratic rule of an African majority being considered an African. Here’s a tree rooted in African soil, nourished with waters from the rivers of Africa. Come and sit below its shade and turn into, with us, the leaves of the identical department and the branches of the identical tree.”

Later within the speech, he reiterated this level much more clearly: “There is just one race to which all of us belong, and that’s the human race.”

Countdown to Sharpeville

Regardless of these lofty beliefs, the PAC was locked in a – typically petty – tussle with the ANC to win the hearts and minds of Black South Africans. Sobukwe launched into a nationwide tour to drum up help for his new get together. And when the ANC introduced its intention to stage an anti-pass marketing campaign on March 31, 1960, Sobukwe resolved to get a bounce on them. He had initially deliberate to launch the PAC’s marketing campaign on March 7, however points with printing flyers pressured him to postpone by two weeks.

Many, together with some within the PAC, thought Sobukwe was being overly hasty and few exterior the organisation might take severely the PAC’s said intention to realize “freedom and independence” for Black folks by 1963. As Mandela put it, “It’s all the time harmful for an organisation to make guarantees it can’t preserve.”

However nobody – bar the apartheid authorities – might blame Sobukwe or the PAC for the bloodbath that occurred at Sharpeville on March 21.

As Mandela put it: “In simply someday, they’d moved to the entrance strains of the wrestle and Robert Sobukwe was being hailed inside and out of doors the nation because the saviour of the liberation motion. We within the ANC needed to make fast changes to this new state of affairs, and we did so.”

On March 26, Albert Luthuli, the ageing ANC chief, Mandela and others publicly burned their passes. Two days later, heeding the decision of the ANC, a whole bunch of hundreds of Black South Africans across the nation stayed away from work in protest towards the killings. As historian Hermann Giliomee writes, “Many whites had been terrified; the Inventory Alternate plummeted, adopted by an enormous capital outflow. With worldwide condemnation of the killings and of the harshness of apartheid coverage, worldwide isolation appeared an actual chance.”

The federal government responded with an iron fist, arresting greater than 18,000 folks and banning the ANC and the PAC. On April 9, in his first public look since Sharpeville, Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd was shot within the face by an English-speaking trout farmer. Whereas Verwoerd was recovering from the assassination try, performing Prime Minister Paul Sauer referred to as for main coverage adjustments, stating “the outdated e book of South African historical past was closed … at Sharpeville”.

For the primary time in years, the liberation motion had a glimmer of hope. However this is able to be short-lived. When Verwoerd bought again to work – he made a remarkably fast restoration – he doubled down, saying a referendum during which he requested (white) South Africans whether or not the nation, which was nonetheless a British dominion, ought to turn into an impartial republic. Verwoerd simply gained narrowly – however when South Africa was declared a republic on Might 31, 1961, the ultimate handbrake to his dream of Grand Apartheid was eliminated.

A person aside

On Might 4, Sobukwe and 17 different PAC leaders had been discovered responsible of “inciting folks to commit an offence” and Sobukwe was sentenced to 3 years in jail, which he served in two jails close to Johannesburg. As the tip of his sentence neared, the apartheid authorities debated what to do with him.

Justice Minister BJ Vorster got here up with a uniquely merciless resolution: he rushed via parliament an modification to the Suppression of Communism Act (SCA) which said: “Anybody convicted below safety legal guidelines might be imprisoned after his sentence had ended if the Minister of Justice thought-about he was doubtless, if launched, to additional the achievements of any of the objects of communism.”

Sobukwe, in fact, was fiercely anti-communist. However the SCA absurdly outlined communism as “any doctrine or scheme … which goals at bringing about any political, industrial, social or financial change”.

No sooner had the modification, which turned often known as the Sobukwe clause, been handed, than Sobukwe was whisked off to Robben Island – the location of the infamous political jail the place Mandela and plenty of others would later be imprisoned – and put in in a small home faraway from the principle jail.

The Sobukwe clause was solely ever used towards one individual – Robert Sobukwe. And he was additionally the one prisoner on Robben Island who was forbidden any contact with different inmates.

In 1969, together with his well being failing, Sobukwe was launched from Robben Island and allowed to stay together with his household in Kimberley – a city he “didn’t know” – below home arrest. There he was topic to banning orders which prohibited him from partaking in any political actions. He did his greatest to get round these restrictions, usually assembly different political figures together with the a lot youthful Steve Biko, whose Black Consciousness motion was in some ways impressed by Sobukwe’s teachings.

After being refused correct healthcare till it was too late, Sobukwe died of lung most cancers on February 27, 1978, and was buried in his birthplace, Graaff-Reinet, at a chaotic funeral led by Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

United States Senator Dick Clark of Iowa, who met Sobukwe in 1976, mentioned after his loss of life: “He was a really light man. Greater than every other individual I met in South Africa, he represented what I had examine: that folks might nonetheless be rational within the demand for change, not bitter. I might hardly perceive it – the shortage of bitterness.”

‘Energy of perception in humanity’

Writing in 2015, Pogrund famous: “South Africa has not been variety to Robert Sobukwe. The magnitude of his deeds and beliefs is basically ignored. The African Nationwide Congress in authorities has finished a lot to airbrush him out of the liberty wrestle. He’s seldom referred to.”

But on his one hundredth start anniversary, South Africa nonetheless grapples with its wrestle to understand lots of the beliefs that Sobukwe espoused.

As Anthony Lewis wrote in his New York Occasions obituary of Sobukwe: “A number of occasions in his life a newspaper reporter meets a political determine and senses genuine greatness: a magnetic exterior presence mixed with a way of internal serenity. That occurred to me on June 9, 1975, within the South African mining city of Kimberley. I met Robert Sobukwe.

“He was despised and rejected by those that maintain energy in his nation. He lived in enforced obscurity, unable to journey, his countrymen forbidden to learn his phrases. However there was an influence in him that shone via all of the petty cruelties of official suppression. It was the ability of perception in humanity, in nonviolent change towards justice, and those that oppressed him ought to pray that it’ll survive his loss of life this week.”